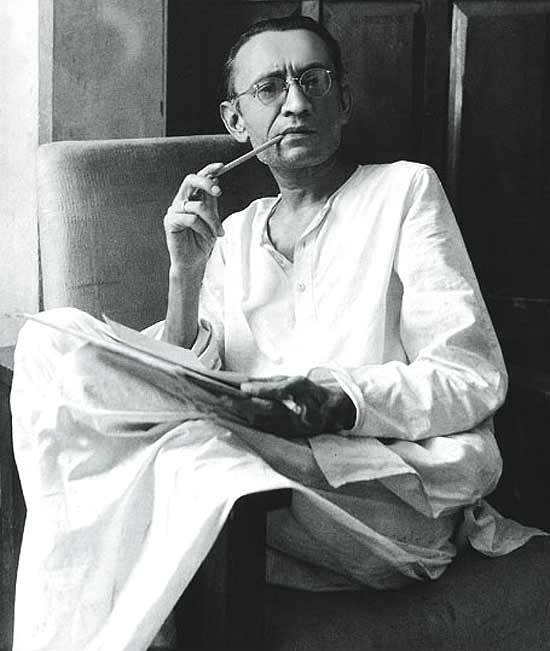

Manto

- navjot2006grewal

- Aug 26, 2024

- 4 min read

Updated: Jan 29

Few films manage to capture the essence of their subject as profoundly as Manto (2018), directed by Nandita Das. The film, based on the life of Saadat Hasan Manto, brilliantly portrays the struggles, brilliance, and heartbreak of one of South Asia’s greatest writers. Nawazuddin Siddiqui’s portrayal of Manto is nothing short of perfection. He embodies Manto’s unapologetic defiance, his vulnerability, and his unflinching honesty with such depth that it feels as if Manto himself has come alive on the screen.

However, what left an indelible mark on me wasn’t just Siddiqui’s stellar performance or the beautifully crafted narrative of Manto’s life. It was the adaptation of Toba Tek Singh, Manto’s searing short story about the Partition of India. That story—and especially its ending—brought me to tears, leaving me emotionally shattered.

Toba Tek Singh is set in the aftermath of the Partition, a time when the subcontinent was violently divided into India and Pakistan, uprooting millions of lives. In this chaos, Manto focuses on an unusual yet deeply symbolic group: the inmates of a lunatic asylum in Lahore. The governments of India and Pakistan decide to exchange not only prisoners and citizens but also the inmates of mental asylums based on their religion. This decision forms the premise of the story.

Among the asylum's residents is Bishan Singh, a Sikh who has been confined for years. Known for his eccentric behaviour and nonsensical mutterings, Bishan Singh is often heard repeating the phrase, “Upar di gur gur di annexe di be-dhiyana di mung di dal of Toba Tek Singh.” This seemingly meaningless string of words references his hometown, Toba Tek Singh, a place he holds dear but which he no longer fully remembers or understands.

As the story progresses, the asylum becomes a microcosm of the larger tragedy of Partition. The inmates, removed from the logic and madness of the outside world, cannot comprehend the absurdity of being uprooted based on arbitrary lines drawn on a map. They question their fate with a childlike simplicity that underscores the cruel irrationality of Partition itself.

The narrative builds to a heart-wrenching climax when Bishan Singh is told that Toba Tek Singh is now in Pakistan. As the day of the transfer arrives, he is escorted to the Wagah border, where the exchange is to take place. Confused and heartbroken, Bishan Singh refuses to cross over to India. He cannot fathom why he is being forced to leave the land of Toba Tek Singh, the land of his memories, the only home he has ever known.

In the final, gut-wrenching moment, Bishan Singh collapses and dies in no man’s land—the narrow strip of ground between India and Pakistan. His lifeless body lies in a space that belongs to neither country, a poignant metaphor for the countless lives uprooted and identities erased by Partition.

That ending struck me like a thunderbolt. It is as if Manto distilled the anguish of an entire subcontinent into this one man’s death. Bishan Singh, a man deemed mad by society, emerges as the only one who truly sees the absurdity of the Partition. His refusal to choose a side—his silent protest—is both tragic and profound. He belongs nowhere, and in that moment, he represents everyone who lost their homes, their families, and their sense of self during the Partition.

What makes Toba Tek Singh so powerful is its simplicity. Manto does not lecture or moralise. Instead, he lets the story unfold with quiet restraint, trusting the reader to feel its emotional weight. Through Bishan Singh’s plight, Manto exposes the dehumanising nature of borders and the folly of dividing people based on religion. The story’s brilliance lies in its ability to evoke laughter and tears in equal measure. It is absurd, tragic, and deeply humane—all at once.

When I saw this story come to life in Manto, it hit me even harder. The film’s depiction of Bishan Singh’s final moments was raw and unflinching. The desolate strip of no man’s land, the chaos at the border, and Bishan Singh’s anguished cries combined to create a scene that was almost unbearable to watch. And yet, I couldn’t look away. It was a moment of pure, unadulterated truth—a reminder of the pain and absurdity of Partition, a wound that continues to fester to this day.

Manto’s Toba Tek Singh remains one of the most powerful commentaries on Partition ever written. Its relevance has not diminished with time; if anything, it has grown sharper. Borders continue to divide us, not just geographically but also emotionally and politically. The story forces us to confront uncomfortable truths about identity, belonging, and the human cost of political decisions.

As for the film Manto, it is a masterpiece that honours the writer’s legacy. By including Toba Tek Singh, Nandita Das reminds us of Manto’s enduring relevance and his unyielding commitment to speaking truth to power. The film, much like Manto’s stories, challenges us to question the world around us and to recognise the shared humanity that transcends borders.

As I reflect on Toba Tek Singh, I am reminded of my grandfather’s stories about the Partition. He would often talk about the friends he lost, the home he left behind, and the pain of being uprooted. Watching Manto brought all those stories rushing back. Bishan Singh’s plight felt personal, his pain a reflection of the collective trauma of my people.

Toba Tek Singh is a mirror held up to history, forcing us to confront its harshest truths. It is a reminder of the cost of division and the enduring power of human dignity. Manto, through his words, gave voice to the voiceless and dignity to the forgotten. And in doing so, he ensured that the stories of people like Bishan Singh would never be erased.

Comments